Improvised Traps and Snares

In a survival situation, your first priority would be to find a sustainable and potable source of drinking water. This is dependent on the environment you are in, for example; if you were in a situation where you needed to make a shelter to protect you from a extreme cold or hot environment that could cause severe injury, then making a shelter would be your immediate priority. Remember that your priorities will change depending on your situation and environment.

Your next priority will be to obtain food to help keep your strength up and also to help keep your immune system working at its optimal level. The longer you go without food the weaker you will become and this will cause your body to reduce its natural disease fighting system to slow down and not work as well. A rule to remember in a survival situation is that you want to expend as less energy as possible when it comes to getting food. This basically means that if it costs you more energy and calories to catch the food than you are taking in, it is not worth the effort. So, the best option for obtaining food without using up a lot of energy and precious calories is to make snares and traps. You will be able to make multiple traps to increase the chances of success.

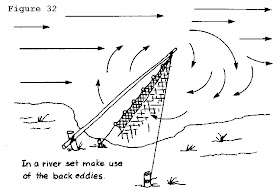

Position your traps and snares where there is proof that animals pass through. You must determine if it is a "run" or a "trail" (read my blog on tracking). A trail will show signs of use by several species and will be rather distinct. A run is usually smaller and less distinct and will only contain signs of one species. You may construct a perfect snare, but it will not catch anything if haphazardly placed in the woods. Animals have bedding areas, waterholes, and feeding areas with trails leading from one to another. You must place snares and traps around these areas to be effective.

Prepare the various parts of a trap or snare away from the site, carry them in, and set them up. Such actions make it easier to avoid disturbing the local vegetation, thereby alerting the prey. Try not to use freshly cut, live vegetation as possible to construct a trap or snare. Freshly cut vegetation will "bleed" sap that has an odor the prey will be able to smell, it could alarm the animal.

Traps or snares placed on a trail or run should use channelization. To build a channel, construct a funnel-shaped barrier extending from the sides of the trail toward the trap, with the narrowest part nearest the trap. Channelization should be inconspicuous to avoid alerting the prey. As the animal gets to the trap, it cannot turn left or right and continues into the trap. Few wild animals will back up, preferring to face the direction of travel. Channelization does not have to be an impassable barrier. You only have to make it inconvenient for the animal to go over or through the barrier. For best effect, the channelization should reduce the trail's width to just slightly wider than the targeted animal's body. Maintain this constriction at least as far back from the trap as the animal’s body length then begin the widening toward the mouth of the funnel.

Use of Bait

Baiting a trap or snare increases your chances of catching an animal. When catching fish, you must bait nearly all the devices. Success with an unbaited trap depends on its placement in a good location and (having something shiny to lure the fish will increase the chances of a catch). A baited trap can actually draw animals to it. The bait should be something the animal knows. This bait, however, should not be so readily available in the immediate area that the animal can get it close by.

For example, baiting a trap with corn in the middle of a corn field would not be likely to work. Likewise, if corn is not grown in the region, a corn-baited trap may arouse an animal's curiosity and keep it alerted while it ponders the strange food. Under such circumstances it may not go for the bait. One type of bait that works well on small mammals is the peanut butter from a meal, ready-to-eat (MRE) ration. Salt, is also a good bait source because animals will usually never this up (it is a hard for animals to find pure salt and they need it just like humans do).

When using such baits, scatter bits of it around the trap to give the prey a chance to sample it and develop a craving for it. The animal will then overcome some of its caution before it gets to the trap.

If you set and bait a trap for one species but another species takes the bait without being caught, try to determine what the animal is so you can then set a proper trap for that animal, using the same bait.

Note: Once you have successfully trapped an animal, you will not only gain confidence in your ability, you also will have resupplied yourself with bait for several more traps.

Trap and Snare Construction

Traps and snares crush, choke, hang, or entangle the prey. A single trap or snare will commonly incorporate two or more of these principles. The mechanisms that provide power to the trap are almost always very simple. The struggling victim, the force of gravity or a bent sapling's tension provides the power.

The heart of any trap or snare is the trigger. When planning a trap or snare, ask yourself how it should affect the prey, what is the source of power, and what will be the most efficient trigger. Your answers will help you devise a specific trap for a specific species. Traps are designed to catch and hold or to catch and kill. Snares are traps that incorporate a noose to accomplish either function.

Simple Snare

A simple snare consists of a noose placed over a trail or den hole and attached to a firmly planted stake. If the noose is some type of cordage placed upright on a game trail, use small twigs or blades of grass to hold it up. Filaments from spider webs are excellent for holding nooses open. Make sure the noose is large enough to pass freely over the animal's head. As the animal continues to move, the noose tightens around its neck. The more the animal struggles, the tighter the noose gets. This type of snare usually does not kill the animal. If you use cordage, it may loosen enough to slip off the animal's neck. Wire is therefore the best choice for a simple snare.

Drag Noose

Use a drag noose on an animal run. Place forked sticks on either side of the run and lay a sturdy cross member across them. Tie the noose to the cross member and hang it at a height above the animal's head. (Nooses designed to catch by the head should never be low enough for the prey to step into with a foot.) As the noose tightens around the animal's neck, the animal pulls the cross member from the forked sticks and drags it along. The surrounding vegetation quickly catches the cross member and the animal becomes entangled.

Twitch-Up

A twitch-up is a supple sapling, which, when bent over and secured with a triggering device, will provide power to a variety of snares. Select a hardwood sapling along the trail. A twitch-up will work much faster and with more force if you remove all the branches and foliage.

Twitch-Up Snare

A simple twitch-up snare uses two forked sticks, each with a long and short leg. Bend the twitch-up and mark the trail below it. Drive the long leg of one forked stick firmly into the ground at that point. Ensure the cut on the short leg of this stick is parallel to the ground. Tie the long leg of the remaining forked stick to a piece of cordage secured to the twitch-up. Cut the short leg so that it catches on the short leg of the other forked stick. Extend a noose over the trail. Set the trap by bending the twitch-up and engaging the short legs of the forked sticks. When an animal catches its head in the noose, it pulls the forked sticks apart, allowing the twitch-up to spring up and hang the prey.

Note: Do not use green sticks for the trigger. The sap that oozes out could glue them together.

Squirrel Pole

A squirrel pole is a long pole placed against a tree in an area showing a lot of squirrel activity. Place several wire nooses along the top and sides of the pole so that a squirrel trying to go up or down the pole will have to pass through one or more of them. Position the nooses (5 to 6 centimeters in diameter) about 2.5 centimeters off the pole. Place the top and bottom wire nooses 45 centimeters from the top and bottom of the pole to prevent the squirrel from getting its feet on a solid surface. If this happens, the squirrel will chew through the wire. Squirrels are naturally curious. After an initial period of caution, they will try to go up or down the pole and will get caught in a noose. The struggling animal will soon fall from the pole and strangle. Other squirrels will soon follow and, in this way, you can catch several squirrels. You can place multiple poles to increase the catch.

Ojibwa Bird Pole

An Ojibwa bird pole is a snare used by Native Americans for centuries. To be effective, place it in a relatively open area away from tall trees. For best results, pick a spot near feeding areas, dusting areas, or watering holes. Cut a pole 1.8 to 2.1 meters long and trim away all limbs and foliage. Do not use resinous wood such as pine. Sharpen the upper end to a point, then drill a small diameter hole 5 to 7.5 centimeters down from the top. Cut a small stick 10 to 15 centimeters long and shape one end so that it will almost fit into the hole. This is the perch. Plant the long pole in the ground with the pointed end up. Tie a small weight, about equal to the weight of the targeted species, to a length of cordage. Pass the free end of the cordage through the hole, and tie a slip noose that covers the perch. Tie a single overhand knot in the cordage and place the perch against the hole. Allow the cordage to slip through the hole until the overhand knot rests against the pole and the top of the perch. The tension of the overhand knot against the pole and perch will hold the perch in position. Spread the noose over the perch, ensuring it covers the perch and drapes over on both sides. Most birds prefer to rest on something above ground and will land on the perch. As soon as the bird lands, the perch will fall, releasing the over-hand knot and allowing the weight to drop. The noose will tighten around the bird's feet, capturing it. If the weight is too heavy, it will cut the bird's feet off, allowing it to escape.

Bird Net

If you have some small netting or you can even use a poncho to catch flying birds. This trap is not always effective, but in a survival situation you need to use any and every method available. Start by placing two long stakes (5-7 feet tall) into the ground. Tie the poncho or netting loosely at the top of the stakes so that if a bird flies into it, the top will collapse over the bird. Tie the bottom of the poncho or netting securely at the bottom, this will ensure the bird does not escape through the bottom area of the trap. The bottom of the netting or poncho should be no higher than 6 inches from the ground. The best time for this trap to work will be in low light level environments like dusk and dawn.

Noosing Wand

A noose stick or "noosing wand" is useful for capturing roosting birds or small mammals. It requires a patient operator. This wand is more a weapon than a trap. It consists of a pole (as long as you can effectively handle) with a slip noose of wire or stiff cordage at the small end. To catch an animal, you slip the noose over the neck of a roosting bird and pull it tight. You can also place it over a den hole and hide in a nearby blind. When the animal emerges from the den, you jerk the pole to tighten the noose and thus capture the animal. Carry a stout club to kill the prey.

Treadle Spring Snare

Use a treadle snare against small game on a trail. Dig a shallow hole in the trail. Then drive a forked stick (fork down) into the ground on each side of the hole on the same side of the trail. Select two fairly straight sticks that span the two forks. Position these two sticks so that their ends engage the forks. Place several sticks over the hole in the trail by positioning one end over the lower horizontal stick and the other on the ground on the other side of the hole. Cover the hole with enough sticks so that the prey must step on at least one of them to set off the snare. Tie one end of a piece of cordage to a twitch up or to a weight suspended over a tree limb. Bend the twitch-up or raise the suspended weight to determine where you will tie a 5 centimeter or so long trigger. Form a noose with the other end of the cordage. Route and spread the noose over the top of the sticks over the hole. Place the trigger stick against the horizontal sticks and route the cordage behind the sticks so that the tension of the power source will hold it in place. Adjust the bottom horizontal stick so that it will barely hold against the trigger. As the animal places its foot on a stick across the hole, the bottom horizontal stick moves down, releasing the trigger and allowing the noose to catch the animal by the foot. Because of the disturbance on the trail, an animal will be wary. You must therefore use channelization.

Figure 4 Deadfall

The figure 4 is a trigger used to drop a weight onto a prey and crush it. The type of weight used may vary, but it should be heavy enough to kill or incapacitate the prey immediately. Construct the figure 4 using three notched sticks. These notches hold the sticks together in a figure 4 pattern when under tension. Practice making this trigger before-hand; it requires close tolerances and precise angles in its construction.

Paiute Deadfall

The Paiute deadfall is similar to the figure 4 but uses a piece of cordage and a catch stick. It has the advantage of being easier to set than the figure 4. Tie one end of a piece of cordage to the lower end of the diagonal stick. Tie the other end of the cordage to another stick about 5 centimeters long. This 5-centimeter stick is the catch stick. Bring the cord halfway around the vertical stick with the catch stick at a 90-degree angle. Place the bait stick with one end against the drop weight, or a peg driven into the ground, and the other against the catch stick. When a prey disturbs the bait stick, it falls free, releasing the catch stick. As the diagonal stick flies up, the weight falls, crushing the prey.

Bow Trap

A bow trap is one of the deadliest traps. It is dangerous to man as well as animals. To construct this trap, build a bow and anchor it to the ground with pegs. Adjust the aiming point as you anchor the bow. Lash a toggle stick to the trigger stick. Two upright sticks driven into the ground hold the trigger stick in place at a point where the toggle stick will engage the pulled bow string. Place a catch stick between the toggle stick and a stake driven into the ground. Tie a trip wire or cordage to the catch stick and route it around stakes and across the game trail where you tie it off. When the prey trips the trip wire, the bow looses an arrow into it. A notch in the bow serves to help aim the arrow.

WARNING: This is a lethal trap. Approach it with caution and from the rear only!

Pig Spear Shaft

To construct the pig spear shaft, select a stout pole about 2.5 meters long. At the smaller end, firmly lash several small stakes. Lash the large end tightly to a tree along the game trail. Tie a length of cordage to another tree across the trail. Tie a sturdy, smooth stick to the other end of the cord. From the first tree, tie a trip wire or cord low to the ground, stretch it across the trail, and tie it to a catch stick. Make a slip ring from vines or other suitable material. Encircle the trip wire and the smooth stick with the slip ring. Emplace one end of another smooth stick within the slip ring and its other end against the second tree. Pull the smaller end of the spear shaft across the trail and position it between the short cord and the smooth stick. As the animal trips the trip wire, the catch stick pulls the slip ring off the smooth sticks, releasing the spear shaft that springs across the trail and impales the prey against the tree.

WARNING: This is a lethal trap. Approach it with caution!

Pit Falls

Pitfalls should be made to the size of the animal you are trying to catch. The larger the animal, the larger the pit fall needs to be. I suggest that you only use small pitfalls to catch animals the size of raccoons, opossums, armadillos, etc. Start by digging a hole approximately 2 feet deep and at least 3 feet wide. Sharpen wooden stakes on one end and then place them at the bottom of the pitfall and ensure they are secure (you can use rocks and line the bottom between the stakes for extra support). The stakes need to be around 6-7 inches long to ensure a killing penetration when the animal falls onto them. Next, cover the pitfall with small thin branches and lightly place a layer of leaves, grass, or other vegetation to fully cover the opening. Place a small amount of bait in the middle of the trap to lure the animal in. When the animal goes for the bait, the animal’s weight will cause them to break through the small branches and impale themselves onto the sharpened stakes. Remember where you put these types of traps so that you do not injure yourself by stepping through them.

Bottle Trap

A bottle trap is a simple trap for mice and voles. Dig a hole 30 to 45 centimeters deep that is wider at the bottom than at the top. Make the top of the hole as small as possible. Place a piece of bark or wood over the hole with small stones under it to hold it up 2.5 to 5 centimeters off the ground. Mice or voles will hide under the cover to escape danger and fall into the hole. They cannot climb out because of the wall's backward slope. Use caution when checking this trap; it is an excellent hiding place for snakes.

Spear Deadfall

Basic to the tripwire deadfall but utilizing rocks to add weight. Once the trap is triggered the added weight will drive the sharpened sticks deep into the animal which will instantly be fatal.

Baited Hole Noose

This trap is very useful for scavengers, first dig a pit approximately 1 foot deep by 1 foot wide. Drive 4 sharpened sticks into the pit through the edges. Lay a noose across them that is attached to a peg outside the pit. Ensure the retaining peg is at least 1 foot long so that you can drive it deep into the ground to ensure that the struggling animal caught in the trap will not pull it free and escape.

Platform Snare

Position the trap over a small depression on a game trail. Snares located on the platforms either side,which when the platform is depressed the trigger is released and the game will be held firmly by the leg. For smaller and lighter game, use the mechanism in figure (a), displacing either the bottom bar or the toggle will trigger the trap.

Leg Snare

Push a natural fork or two sticks tied together into the ground. The line from a sapling is tied to a wooden toggle and the toggle is passed under the fork. When the game takes the bait attached to a separate stick, it falls away releasing the toggle which flies up taking the snare and the game with it. Large versions of this trap are amongst the best snares for heavier game.

Trip Wire Deadfall

A heavy log is suspended over a heavily used game trail. The animal trips the wire and pulls a retaining bar from under two short pegs secured in a nearby tree trunk. Try to make the pegs as short as possible so that the bar will disengage easily when the animal trips the wire.

KILLING DEVICES

There are several killing devices that you can construct to help you obtain small game to help you survive. The rabbit stick, the spear, the bow and arrow, and the sling are such devices.

Rabbit Stick

One of the simplest and most effective killing devices is a stout stick as long as your arm, from fingertip to shoulder, called a "rabbit stick." You can throw it either overhand or sidearm and with considerable force. It is very effective against small game that stops and freezes as a defense.

Spear

You can make a simple spear to kill small game and to fish with. Jab with the spear, do not throw it especially if you are using a knife or other potentially valuable tool because of the chances of loosing or damaging it (you may need this item).

Bow and Arrow

A good bow is the result of many hours of work. You can construct a suitable short-term bow fairly easily (if it loses its spring or breaks, you can replace it). Select a hardwood stick about one meter long that is free of knots or limbs. Carefully scrape the large end down until it has the same pull as the small end. Careful examination will show the natural curve of the stick. Always scrape from the side that faces you or the bow will break the first time you pull it. Dead, dry wood is preferable to green wood. To increase the pull, lash a second bow to the first, front to front, forming an "X" when viewed from the side. Attach the tips of the bows with cordage and only use a bowstring on one bow.

Select arrows from the straightest dry sticks available. The arrows should be about half as long as the bow. Scrape each shaft smooth all around. You will probably have to straighten the shaft. You can bend an arrow straight by heating the shaft over hot coals. Do not allow the shaft to scorch or bum. Hold the shaft straight until it cools.

You can make arrowheads from bone, glass, metal, or pieces of rock. You can also sharpen and fire harden the end of the shaft. To fire harden wood, hold it over hot coals, being careful not to bum or scorch the wood.

You must notch the ends of the arrows for the bowstring. Cut or file the notch; do not split it. Fletching (adding feathers to the notched end of an arrow) improves the arrow's flight characteristics, but is not necessary on a field-expedient arrow.

Sling

You can make a sling by tying two pieces of cordage, about sixty centimeters long, at opposite ends of a palm-sized piece of leather or cloth. Place a rock in the cloth and wrap one cord around the middle finger and hold in your palm. Hold the other cord between the fore finger and thumb. To throw the rock, spin the sling several times in a circle and release the cord between the thumb and forefinger. You will need to practice to gain proficiency and be able to hit your target. The sling is very effective against small game.

Flint Knapping

Flint Knapping is an age old technique used by our primitive ancestors to make spear tips, arrow tips, and cutting tools. This art does take a lot of practice to become good and make really nice things with, but in a survival situation can be used to improvise tools good enough to get the job done. Flint Knapping uses chipping and flaking techniques on rock forms to slowly sharpen and create points that you can attach as spear heads, arrow heads, or use as cutting or digging tools. This is an extremely valuable skill to learn and is well worth the time it takes to get good at it.

NOTE: The use and construction of any of these traps, snare, deadfall, and pitfalls should be done only under responsible adult supervision.Extreme caution should be taken with proper safety and safety equipment because these can and will cause severe bodily injury or even death. This is for educational purposes only!